Te Whare Pora: House of Learning

An essay written by Dr Awhina Tamarapa on Te Whare Pora: House of Learning, an exhibition featuring the work of Roka Hurihia Ngarimu-Cameron MNZM. Te Whare Pora: House of Learning is on display in WHAKAARI from Saturday 8 June - Sunday 28 July 2024.

Te Whare Pora | He Whare Wānanga, Hei Whiria i ngā Tāngata

The House of Weaving | A House of Learning, Weaving People Together

Matariki hunga nui — Matariki of many people

The Māori New Year is celebrated between June and July, at the rising of the open star cluster known as Matariki, or Pleiades. It is a time to reflect on the past, celebrate the present and plan for the future.

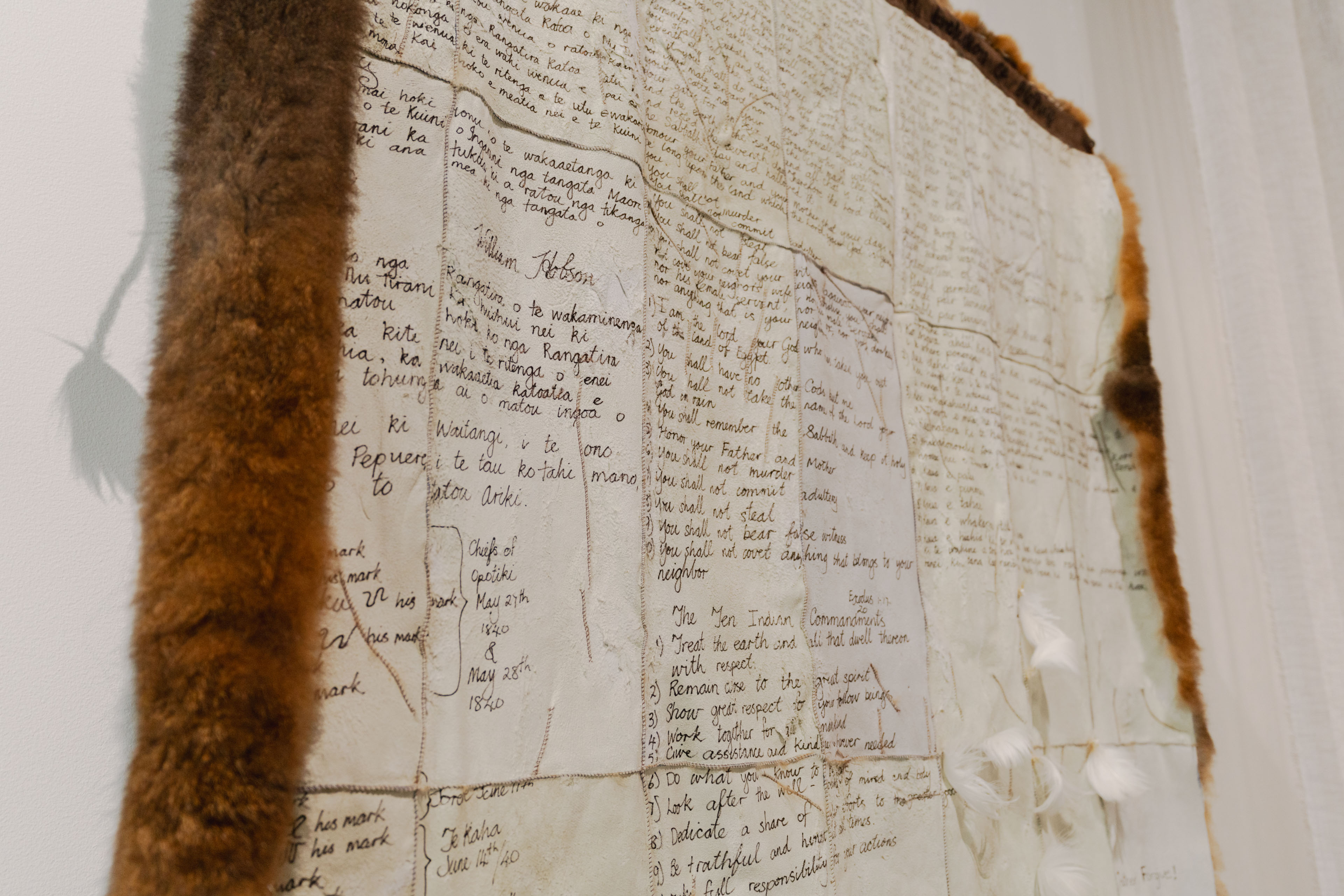

Te Whare Pora the exhibition, acknowledges the mana (authority) and mauri (life essence) of Māori weaving, through the sublime artistry of master practitioner and teacher, Roka Hurihia Ngarimu-Cameron. Every hand-spun fibre, soft feather, velvety leaf, pelt, and delicate stitch, connects to the natural world. Papatūānuku, Earth Mother, in all her bounty, receives new life through Roka’s cultural knowledge, creativity, and skills. The exhibition reflects on Roka’s journey, celebrates the present with her family and weaving students, and invites us to think about a healthy, vibrant world for future generations.

Whiria ngā whenu, hiki i te wairua — Braid the connective threads to lift the spirits

The main themes of the exhibition—taking care of people and the natural environment— are important to Roka. Raised amongst her people of Te Whānau ā Apanui, within the Hāwai marae papakainga (original home), ancestral ways of knowing and being were installed from a young age. Kaitiakitanga (custodianship) and manaakitanga (care of people) are attributes of tangata whenua (people of the land), living for generations in Aotearoa. The 1950s drift into urban areas for employment had an impact on rural communities, resulting in loss of cultural identity and familial structures. Roka and her family have helped people in recovery, through wrap-around pastoral services.

Roka shows connectivity flows through her artforms. Having established three weaving schools and a lectureship at the University of Otago, Roka was encouraged to pursue a Master of Fine Arts at Te Kura Matatini ki Otago/Otago Polytechnic, completed in 2008. While on campus, Roka was drawn to a forlorn-looking loom in a corridor. She was reinvigorated with the idea of adapting the ancient whatu (finger weft twining) technique using hand processed whītau (inner harakeke or NZ flax fibre) woven on a loom. Bringing both traditions together is an incredible achievement. The amalgamation is a metaphor for interculturalism, her “creative response to my dual heritage.”

Te Whare Pora — The House of Weaving

Māori weaving is a strong cultural thread that has woven the people and environment of Aotearoa together for over eight hundred to nine hundred years. It is a revered, sacred practice that embodies cultural values, knowledge and customs. As a living artform, it has aspects that are activated through ritual and protocol. According to master weaver Erenora Puketapu-Hetet “[w]eaving is endowed with the very essence of the spiritual values of Māori people. The ancient Polynesian belief is that the artist is a vehicle through whom the gods create.” The range of technologies include whatu (finger weft twining), taaniko (coloured horizontal threads weft twined in the whatu technique), whiri (braiding), raranga (plaiting), whāriki (mat weaving) tukutuku (lattice weaving) and tuitui (stitching).

Māori weaving is connected to the natural world by core concepts, such as whakapapa (genealogical connections), mauri (life principle, energy), tapu (sanctity). The disciplines of weaving have been influenced by access to resources, time, skill and purpose. The first arrivals from the Pacific would have recognised similar plant fibre for weaving. The luxuriant fan-like leaves of the harakeke (NZ flax) plant were quickly utilised for basketry, rope and binding. The whatu (finger weft twining) technique was adapted from net and fish trap making to garment construction, replacing the paper thin, beaten aute or paper mulberry tree bark as cloth. Technological adaptions enabled our ancestors to survive the cooler, temperate climate.

Māori weaving is a cultural pedagogy, a form of Indigenous teaching, that “generates knowledge, shapes values and constructs identity.” Weaving terms, such as ‘te aho mutunga kore,’ the eternal thread, is a metaphor for the unbroken genealogical connection of Māori people. ‘Whenu,’ the warp threads of a cloak, is also a term for land and the umbilical cord that connects a mother to her unborn child. The harakeke or Phormium tenax plant symbolises a whānau, the central shoot the ‘rito,’ or baby. These beliefs are important in Māori culture.

Taonga puoro, taonga Hauora — Singing treasures, restoring well-being

Taonga are highly valued objects, knowledge, practices, places, resources and cultural aspects that link to ancestral history, customs, spiritual beliefs and worldview. Taonga are tangible and intangible expressions of what is uniquely Māori, imbuing a sense of cultural identity and belonging.

Taonga puoro are the rhythmic and wind instruments of Māori ancestry, sourced from the sounds and materials of nature. They were used to perform ceremonies, mark events and make announcements. They were used for healing and communication between people and the spiritual realm. Like many forms of Māori art and practice, taonga puoro went into decline during the 19th century. About 30 years ago, a ‘renaissance’ began—led by the late song writer, musician and scholar from Ngāi Tūhoe, Hirini Melbourne, the late Richard Nunns, from Nelson, a talented jazz musician and teacher, and Brian Flintoff, a bone and stone carver and teacher, also from Nelson. They formed the revivalist group named Haumanu, meaning ‘breath of birds.’ The group began a community based recovery of taonga puoro, a precious taonga tuku iho (heritage passed down) by talking to elders, making and playing instruments, and sharing knowledge through wānanga (intensive learning) on tribal marae (Māori community place/complex).

Ka puta ngā huarahi o ngā tūpuna — Ancestral pathways appear

Te Whare Pora is a celebration of Roka Hurihia Ngarimu-Cameron, her weaving pedagogy and legacy for the future. Roka honours Papatūānuku, Earth Mother, pays homage to the people of the land and the healing frequencies of taonga hauora. The exhibition is enveloped in the undulating Southern forms of Papatūānuku. This is a tribute to the tenacity of ancestors whose footsteps are traced, whose visual language remains as powerful connectors within a house of learning.

Roka’s innovative research practice is documented in her Masters dissertation, Toku Haerenga (2008).

Her journey casts back to the foundations of Māori weaving. Roka not only traces the adaption of garment technology over time, but the tikanga (customs and values) and deeper knowledge inherent in Māori practice. Her work explores ancestral pelting and tanning methods and honours the Aboriginal peoples sacred taonga, possum skin cloaks. Roka’s work is now woven into the genealogy of Māori cloak weaving, by bringing on-loom practice into the folds of Papatūānuku. The connecting thread is that of the harakeke plant and its silken, strong fibre, aptly described by Roka as the “thread of life, te aho ora.”

Finally, in the words of Roka herself;

It is from Papatūānuku that I derive the inspiration of my art. In my use of the physical materials provided from her bounty, the idea is that she…would express herself through the work of my hands.

My work should be viewed therefore, as a celebration and honouring of Papatūānuku and a plea for manaaki whenua – for conservation and the care for the environment.

E te Mareikura, te raukura whatu i te tangata, hāpaitia ngā taonga Rangatira, i waiho iho rā, e ngā mātua tipuna.

Dr Awhina Tamarapa, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Ruanui, is formerly Curator Māori at Te Papa. She is now a Postdoctoral Research Fellow based at the Stout Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington.

Credits:

Video and photography: David Oakley

Soundscape: Te Ku Te Whe by Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns. Courtesy of Songbroker Music Publishing and Rattle Records NZ

With grateful thanks for generous support:

Creature Post

Dougal Austin, Senior Curator Mātauranga Māori, Te Papa Tongarewa

Glen Russell

Oraka Aparima Runaka

Sto Plaster

Te Pūkenga

Treology

Te Wānanga o Aotearoa

1 Ngarimu-Cameron, Rokahurihia. 2008. Toku Haerenga. Masters dissertation. Pg.1.

2 Puketapu-Hetet, Erenora. 1989. Maori Weaving/with Erenora Puketapu-Hetet. Auckland: Pitman. Pg.2.

3 Kincheloe, Joe and Peter McLaren. 2000. “Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research”. In The SAGE handbook of

qualitative research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 2nd edition, 279–314. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Pg.285.

4 Puketapu-Hetet, Erenora. 1989. Maori Weaving/with Erenora Puketapu-Hetet. Auckland: Pitman. Pg.2.

5 Tamarapa, Awhina. 2015. The Role of a Museum (Te Papa) in the Rejuvenation of Taonga Puoro. MA Thesis. Pg. xii.

6 Flintoff, Brian. 2004. Taonga Puoro: Singing Treasures. Nelson,N.Z. Craig Potton Publishing.

7 Ngarimu-Cameron, Rokahurihia. 2008. Tōku Haerenga. Masters dissertation, Otago Polytechnic. Pg.58.

8 Ngarimu-Cameron, Rokahurihia. Date unknown.

Click here to listen to Rokahurihia Ngarimu-Cameron speak to RNZ about Te Whare Pora.